Why do we need female health education?

KNOWLEDGE IS POWER! Giving females knowledge to understand their cycle allows them to form a perspective and help them plan their exercise and training around it.

Right now, approximately 53% of female athletes are taking hormonal contraceptives, but only 20% were able to tell you what the female sex hormones are (4)!

What should we be teaching?

The basics! This includes, what a normal cycle looks like, what symptoms of dysfunctions look like and what to do about it. Education should also include information about manipulating the menstrual cycle with hormones (such as skipping periods with the pill).

What are the basics?

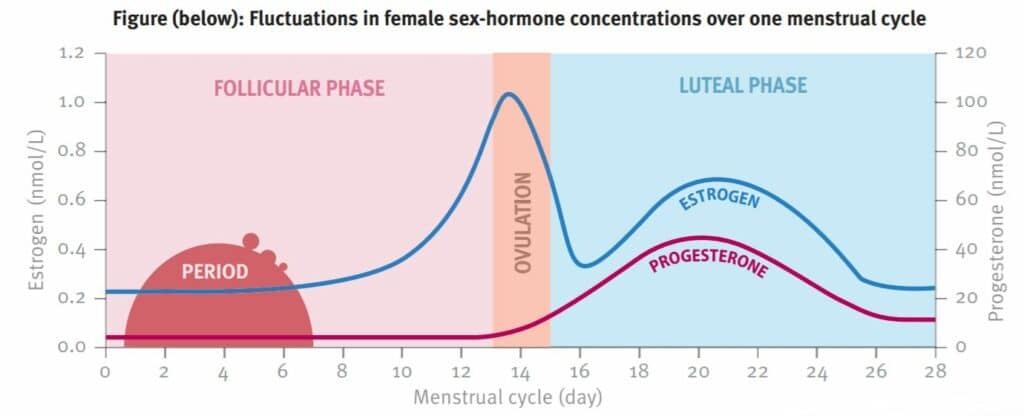

The menstrual cycle is a monthly cycle of changes in sex hormones (oestrogen and progesterone). The average cycle lasts 28 days but a normal cycle can range from 25-35 days. There are three phases of the cycle that all females should understand.

Follicular phase

- Lasts from first day in the cycle to roughly the 14th day

- Menstrual period (bleeding) occurs

- Can last for 4-7 days

- Anything longer than 8 days is not normal and should be referred to a health professional

- Low levels of oestrogen and progesterone

Ovulation phase

- Begins around the 13th day in the cycle

- High levels of oestrogen and progesterone

Luteal phase

- Begins around day 15

- Elevated levels of oestrogen and progesterone

Cattelini

Dysfunction

The term dysfunction relates to abnormal cycles. Abnormal cycles are generally experienced more by athletes than sedentary populations. Evidence suggests that between 16 and 64% of female athletes experience menstrual dysfunction. Commencing hormonal contraception at an early age (before the menstrual cycle falls into a regular pattern) can increase the chance of dysfunction symptoms being missed.

Cattelini

Potential conditions include:

- PCOS (ovarian cysts)

- POI (early menopause)

- Ovarian tumors

- Turners syndrome (underdeveloped ovaries)

- Malignancy (presence of a malignant tumor)

- Thyroid dysfunction

What is hormonal contraception?

Hormonal contraceptives are synthetic female sex steroids used to suppress the natural female sex hormones. There are many types on the market such as the following:

Cattelini

Prevalence

It is estimated that about 80% of females will take some form of hormonal contraception in their lifetime for several reasons.

- Birth control/ contraception

- Manipulate menstrual period

- Lighter periods

- Reduce symptoms such as cramping and bloating

- Maintenance of conditions such as endometriosis

Risks and Outcomes

While studies have shown that hormonal contraceptives are safe for use, there are a few things to consider, particularly for athletes who may be more susceptible to injury (3).

- Taking hormonal contraceptives before total development can negatively affect bone health

- Evidence suggests sleep recovery is impaired when taking oral contraception due to the effect on sleep cycle

- Increasing load during follicular phase has shown to be more beneficial than loading in the luteal phase due to hormone levels

- Taking hormonal contraception before the menstrual cycle has fully established can cause issues later on such as:

- Failure to notice dysfunction

- Longer return to a normal cycle after stopping hormonal contraceptives (can take up to several years)

How can we teach this?

Effective conversation

- Ensure knowledge on both sides (coach/ professional/ support systems and females)

- Is the environment safe and open?

- Is there an opportunity to have this conversation?

Fundamentals

- Time the conversation well

- Actively listen (open ended questions, affirm, reflect, summarise)

- Share ownership of the topic

- Treat the topic as if it’s an injury (be clinical rather than personal)

- Decide what action to take together

Resources

- Infographics

- Network for contacting professionals

- Links to established sources

- Workshops and presentations

- Teach monitoring and tracking

- Role play conversations

- Get comfortable talking about it

When should females learn all of this?

Early! Normalise periods and menstrual cycles as soon as you think the girls can handle it. Early education and intervention helps females make good decisions and form perspective about their health. Education allows females to take responsibility for their own body with tracking, monitoring symptoms and speak up when something isn’t right.

Male role models

There are obvious barriers when it comes to male role models discussing female health. Particularly in a sport setting, female athletes may feel uncomfortable discussing health concerns with male coaches, more so in the younger years. There are some suggested methods to try in overcoming these barriers.

- Use clinical methods such as screenings and questionnaires

- Ask athletes to start monitoring their cycle and symptoms in an app or diary for training purposes

- Build off the tracking to get the conversation started in a clinical and factual manner

- For example: “I noticed that your cycle has been extremely irregular over the last few months according to your tracking notes. Have you spoken to a GP about this?”

- With language like this, you aren’t asking them to explain or give details, but getting the message out there that it’s an acceptable topic of conversation and it’s okay to discuss in this environment.

Keep it clinic, professional and take the personal out of it. Pretend they are your patient and you don’t know them. Laying down a foundation of openness and factual conversation can remove the awkwardness or feeling of embarrassment, especially for younger females.

I hope this blog has given you an understanding about female health and the steps we need to take as professionals and even parents for our female population. For more information, ESSA has published a great eBook all about Women’s Health which I highly recommend getting your hands on.

Written by Courtney Tebbutt (Assistant Physiotherapist)

References

- Dadgostar, H., Razi, M., Aleyasin, A., Alenabi, T., & Dahaghin, S. (2009). The relation between athletic sports and prevalence of amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea in Iranian female athletes. Sports medicine, arthroscopy, rehabilitation, therapy & technology : SMARTT, 1(1), 16.

- Klentrou, P. & Plyley M. (2203). Onset of puberty, menstrual frequency, and body fat in elite rhythmic gymnasts compared with normal controls. Br J Sports Med, 37(6). 490-494.

- Mudd, L. M., Fornetti, W., & Pivarnik, J. M. (2007). Bone mineral density in collegiate female athletes: comparisons among sports. Journal of athletic training, 42(3), 403–408.

- Periera, H. M., Larson, R. D. & Bemben, D. A. (2020). Menstrual cycle effects on exercise induced fatigability. Frontier Physiology, 11, 1-9.